- Home

- Elizabeth Knox

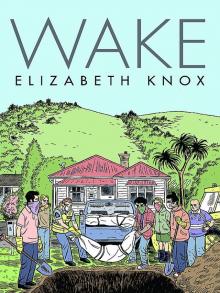

Wake Page 25

Wake Read online

Page 25

Myr had explained to Sam why he was in Kahukura. And, although his explanation was strange, dislocating, and in translation, it was also at first oddly comforting. It gave Sam comfort because it made sense, and encouraged her to stop thinking of the monster as hers. The monster was Myr’s; he was its keeper, its jailer. It had a provenance, and Myr had protocols for it. He might be an alien, but provenance and protocols were the world Sam knew.

Myr untied her, and then, as she sat ostentatiously rubbing her wrists, he settled by the fire and started to talk. He spoke slowly, choosing his words carefully. Sam listened and understood that he was taking pains in explaining to her, and that all his facts appeared to her detached from words and terms that were important to him. Using Sam’s language, Myr told her about his monster. The Wake.

‘I will begin in the traditional way,’ he said. ‘Once upon a time, my people had things—devices and ideas—which, for the purposes of this story, I will call Finders. These Finders were the glory of our civilisation. For, although our lives are short, too short for what your people would call “a life’s work”, we have always been able to do a great deal. If we had been confined to the culmination of many short lives of labour, then our civilisation wouldn’t have progressed much further than a village existence, raising gardens, planting orchards, for—think—how much is studied, digested and reflected upon by any of your people within their first thirty years? Thirty years is an average lifespan for us. However, when my people sleep—which they do fifteen hours out of any twenty-four—they dream.’

‘Oh,’ said Sam. ‘That’s why we haven’t been able to find you. You’ve been asleep most of the time.’

‘Yes.’

‘Sorry,’ said Sam. ‘I interrupted you.’

Myr drew breath to go on. But Sam had another thought, and interrupted again. ‘So how old are you?’

‘I don’t know,’ Myr said. ‘But I haven’t entered my late-flowering. You see—we have several years of brilliance before we die—then go quite abruptly. Our whole system collapses within a few days.’

‘You must have some very strange traditions,’ Sam said. ‘And here you are indulging me with “Once upon a time”.’

Myr gave a respectful nod. ‘I am pleased to indulge you if it helps me persuade you to trust me with your own special knowledge,’ he said, then continued his explanation. ‘Insights would come to my people in their dreams. Understandings, formulas, and plans for devices that could “find” whatever we might want or need. Whatever we lacked, our dreams supplied. And what we came to believe about ourselves was that the universe was giving us gifts. That the universe came into our dreams like a loving mother coming in to kiss her sleeping children.’

Sam said, ‘Sorry, I’m not quite getting these Finders.’

Myr gave examples. ‘My people have water Finders that pull abundant clean water out of thin air—or, in fact, from some other part of the universe. We have energy Finders that open gaps through to some pure energy entity—a latently sentient thing that seems only to want an invitation in order to flow through and act kinetically and make things work, an entity that seems simply to delight in making things run in a solid material world.’

‘All right,’ Sam said. ‘But my people only know about energy without a brain in its head. So this is hard to imagine.’

‘Is it?’ said Myr. ‘Even though you have felt your energy leaving you when you walk into my quarantine field?’

He meant the No-Go. ‘Your quarantine field isn’t an entity, is it?’

‘It’s powered by one.’

‘Oh,’ said Sam. She was beginning to get an itch of understanding—and it frightened her.

‘Then one day,’ Myr said, ‘someone by accident made a Finder that invited a monster to come through to them, a monster that worked on minds, and drove people mad, and fed on the resulting chaos. The monster killed almost all of my people—all but those who for some reason were undetectable to it. It seemed not to know they were there. These survivors were, for the most part, people who’d never been able to find things in their dreams, people who were, in the terms of my world, disabled.’

‘You?’ said Sam.

Myr nodded. ‘We survivors, the disabled and the very few surviving able, might have chosen to go on as we had, making gardens and purposely playing away our lives, following dreams and finding further treasures. But, instead, we decided to locate the monster—which we named the Wake. We chose to find the Wake, follow it, and make sure it didn’t do any more damage, didn’t come back to finish what it had begun, or go somewhere else and do to other people what it had done to us. For my people understood that though the Wake had gone, it had gone on, making its way through all the invitations we had sent throughout our history. Invitations we made to a supposedly wholly beneficent universe.’

‘So this happened in your lifetime?’

‘No. I say “we”, but I wasn’t there. I’m a descendent of survivors. Many generations removed.’

‘Your people have been following this monster for generations?’

‘These monsters. Plural. My ancestors’ decision to send volunteers out after The Wake to help other people on unknown worlds was less altruism than a religious response. The way they saw it was this—if for all those years they had been chosen and nurtured, then they should show gratitude by at least trying to mend their mistake. That’s our mission—to mend our mistake. Only it has turned into damage control. The original Wake was almost impossible to stop. And, of course, there were other Wakes with the same singular vicious practices—monsters slipping through every opening my people had made.’

Myr paused and waited for Sam to meet his eyes. Once she had, he went on. ‘Some years ago I relieved another of my people from the task of following this Wake. I pursue it, catching it up as it alights and begins to feed, and keeping it corralled so that it can’t spread from its entry point to engulf a whole world—as its kin engulfed our world.’

Sam bit her bottom lip and stared at him.

‘You have something to tell me,’ he said.

‘You were here before. We’ve seen the rock drawings. We know that you were here before.’

Myr nodded. ‘This monster, my Wake, is moving through a string of linked worlds in the mathematical and material regularity that your people call “space-time”. Or, more accurately, the Wake doesn’t move its whole self between worlds, since only part of it touches down. The rest of it remains where it belongs, out in the “between”, a place where there is no time, or possibly where there is all time. My people aren’t sure which it is—no time or all time—because though we follow these monsters, or their incursive bits, from world to world, we aren’t conscious in the between, and can’t make observations.’

Sam recognised this ‘between’ Myr was talking about as the place she went when she wasn’t here. She imagined the monster in that place with her, brushing against her static, breathless body. A vast rapacious thing, with its glassy proboscis thrust through to dabble at the dark earth of Adele Haines’s grave, like a cat searching its empty plate for any overlooked crumbs. Sam could see Myr was about to forge straight on with his explanation, so she interrupted again. ‘Wait,’ she said.

Myr didn’t want to be interrupted. He tried to make himself clearer. He looked impatient. ‘We don’t know how this Wake got into this particular string of worlds.’ He paused, then said, with an air of delicacy: ‘Though you might prefer to think of them as “alternate realities” rather than “multiple worlds”.’

‘Might I rather?’ said Sam.

Myr leaned forward, eager. ‘When I follow my Wake I always find myself somewhere like here, in a place that corresponds to this place. This is where the connection is. This is where there was a weakening—an event, an invitation.’

‘You really were here four hundred years ago?’ Sam said, again, when he paused for breath.

‘Yes. The Wa

ke comes here, and other places almost exactly like here. An insular nation, remote from other landmasses, with these plants, this rain, these mountains hard up against the sea, this large shallow bay, and these birds singing these songs.’

It was near dawn and the birds were singing. There was light coming through a crack in the curtains.

Sam thought for a bit. There was a stealthy little tumble of coals in the firebox, and the light altered. She was forming a horrible suspicion, and she must make absolutely certain she understood him. If he was here four hundred years before, that didn’t mean he was very old. He’d just told her that his people had short life spans. No—someone had opened a door on what was outside of space and time, and the Wake had come in, and was now tunnelling along a series of worlds not just linked, but whose links were produced by that ‘invitation’. The Wake originated in the between, the between where she was stored whenever she went away.

Sam knew about Myr’s ‘between’. She understood Myr and believed him—though, like him, she was only ever between for an instant, and unconscious when she was. She’d come back, and drops of water from Samantha’s skin would settle on hers when she arrived. (Only, her hair would never quite take the wet in a natural way. Instead of dripping, it would look more as if she’d been buffeted by windblown drizzle.) There was a slight displacement of dust or water, sweat or blood, but no real sign of the change. And because there was no sign, no evidence, Sam would sometimes play tricks on the other Sam. For instance, there was the one time she’d been so angry with her blameless sister that she cut her own hair off. Samara did those things because she was the one who had to pretend, to pretend to be stupid, because the other Sam could hardly be expected to pretend to be clever. So Samara had played tricks on her sister, but when she arrived even her sister’s sweat would accommodate her and no one knew and, of course, the whole thing was hateful to her so she stayed away, and let the other Sam live her inoffensive life—

—and then she had appeared in the smoke-filled kitchen at Mary Whitaker, in blood-soaked clothes, to find herself standing at the stove, tending a spitting paella pan full of fried human nipples, one of them as familiar to her as her own. She arrived with the chilly, inorganic smell of between on her, into Samantha Waite’s suddenly untenable life. ‘And now,’ Sam thought. ‘Before I lose my mind altogether, I have to make sure I completely understand what I’m being told.’

Myr was sitting cross-legged on the floor in front of the white leather recliner, watching her. When she looked at him he said, ‘Yes, I had expected tears.’ Clinical, as if he were checking symptoms.

Sam wiped her eyes, and said softly to herself: ‘It was what was done to us.’ She meant that it was whatever Uncle and the woman had done to separate her and her sister that had opened the door for Myr’s Wake.

But when she said ‘It was what was done to us’, Myr apparently thought that she was comparing the survivors’ current situation to that of the Ngati Tumatakokiri who had buried their dead in storage pits. ‘Yes, many of the same things happened to those people,’ he said. ‘They were in quarantine. It rained for three months, and they invited me into their homes.’ He waited for another question, and in the silence a look of desperation crossed his face. He said, ‘If the Wake isn’t trapped it will spread everywhere, feeding on human madness, zeal, and ecstasy. If I don’t trap it, it kills everyone.’ He sounded as if he was pleading for her understanding.

‘It was us,’ Sam said again. ‘We did it.’

He didn’t—and couldn’t—understand her. He said, ‘You didn’t do anything. You and your companions only survived because you all arrived after the Wake had finished its first feed.’

Sam’s ears were ringing. She was thinking two things. One was immediate and relative: if the Wake had finished feeding, then why did Myr still have it trapped? The second was that she must find out for sure whether she was in any way to blame. She tried to formulate a question. She felt her life depended on the answer.

‘Space and time are one thing—space-time—like Einstein said. So, am I right in thinking that, when the Wake jumps from world to world, it can move not just between worlds but between times? It can go backwards and forwards in time? And so the thing that invited it in needn’t be something that happened a long time ago, it might even have happened recently?’

Myr frowned. ‘That is a very odd question—given others you could ask. To answer—my people don’t know whether time travel to the past is possible. We haven’t had any insights. All these monsters move forward in time, but between worlds, and sometimes they skip hundreds of years. This Wake has been on the move for much longer than I have been following it. And for much longer than the person from whom I inherited the job. It was once more robust. But my people have followed it vigilantly, and starved it. We have starved it from place to place. Sometimes we’re lucky and it alights where there are no people. It can’t get any sustenance from birds and reptiles, and it has to jump again without feeding. That has helped.’

Sam laughed, and Myr looked startled. It was a laugh of relief. She wasn’t culpable. The Wake was going from world to world, but always forward in time. She and Fa, Uncle and that stranger—it hadn’t been them, what they did, and what was done to them. Sam ground her fists into her damp eye sockets and laughed. ‘Not guilty,’ she said.

Myr must have supposed she meant him. That she was laughing at his attempt to exonerate himself, to say that although he had the survivors trapped and separated from their families, he was only doing his duty. Because that was what he was saying.

He was watching her, waiting for something. Sam couldn’t tell what. Then she had a thought. She asked another question—and could see as soon as she did that it wasn’t the one he was waiting for. ‘Are all of your people like you?’ she asked. ‘Very dark?’

He looked a little disapproving. ‘I have come to see over the years that your different skin colours inspire attitudes that cause social complications.’

‘That’s not an answer.’ Sam scowled at him and gnawed her lip. ‘And, by the way, we have “attitudes” to all our differences.’

‘Yes. The answer is that my people are all variations on this colour.’

Sam was thinking of the woman who had come to visit Uncle just before she and her sister were separated. She was making a connection, but had to check some facts before jumping to conclusions. ‘Your life isn’t continuous, right? I mean, because you’re following the Wake, your timeline doesn’t match up with that of any other world, even your own.’

Again he looked surprised. ‘You are very astute. And the fact that my life isn’t continuous is a matter of more significance than my skin colour.’

‘You follow the Wake between worlds, skipping over years and sometimes even centuries. Am I right?’

‘Yes.’

‘So you’re not in touch with your own people?’

‘No. I can see that you are worried—but there are numerous possible points in this Wake’s path where I can be relieved. My life will come to an end, but this Wake will not go unguarded.’

‘But you are currently out of touch and have been for some time?’

‘Yes, mine is a solitary vigil.’

Sam didn’t reply. She was thinking that if Myr’s people had come up with a new strategy for dealing with these monsters, Myr might not know about it.

If only Uncle had confided in her. But after the other Sam was injured and damaged he had become distant and dictatorial. Had he supposed the plan would fail—if there was a plan? Had the other Sam’s mental impairment made him lose faith in her own ability to understand things?

She would never know. Uncle had died of a heart attack when Sam and her sister were in their mid teens. And she hadn’t even been there to notice warning signs and start asking the questions that she needed answers to, now more than ever.

Sam had a feeling that there was something else

she’d meant to ask Myr—something vital. She looked at the fire. The log that had tumbled in the grate had fallen apart and its coals shimmered, so hot that the smoke rising from them formed above their surfaces. Each coal lay in a halo of hot, smokeless air. These bubbles of clarity reminded Sam of the No-Go, and she remembered what it was she’d meant to ask. ‘Why is your quarantine still in force? Why is the Wake still here?’ Then, ‘That’s a translation, isn’t it? “Wake” is just a word you’ve chosen—a word in my language.’

Myr nodded.

‘Is it “wake” as in “wake of destruction”?’

‘No, it is “wake” as in “a feast in the presence of the dead”. And that should give you your answer. The Wake powers the quarantine zone—though it doesn’t know it. The zone won’t vanish till the Wake moves on. The devices that form the zone are deep inside it. The Wake leaves, and, without a power source, the zone disappears. I gather up the devices, and go after the Wake.’

Sam frowned at him. She was trying to imagine his life. ‘Don’t you get lonely?’

A spasm of feeling passed across his face. Sam was unsure what it meant. She said, ‘You could join us. Look—you’ve explained. You’ve exonerated yourself. I can convince them not to shoot you.’

Myr shook his head. ‘You haven’t understood. I’m only talking to you because you’re different. You know the Wake is here. That’s unprecedented. That’s something I have to investigate.’

Sam wanted Myr on hand—and safe. She thought she would probably confide in him eventually. But first she needed to think things over in private. She said, ‘You’re interrogating me, so I can’t be kind to you? Is that what you’re saying?’

Myr moved forward. He took her hands. ‘Think.’

Sam sighed and stirred as if she was trying to shield herself from a cold, ticklish breeze.

‘The fact that you know the Wake is there isn’t a hope,’ Myr said. ‘It’s only something different. You ask which meaning of your word “wake” I’m using, and I say “a feast in the presence of the dead”, and you still don’t understand me. You ask me whether I’m lonely. Let me tell you, loneliness is better than the death-watch. The Wake comes, it causes madness and terror, and it gorges itself. That’s its sustenance. Then it savours what’s left. It cleans its plate. That’s what always happens. The only differences are in what I do. And I’ve tried everything. I’ve remained aloof, and I’ve gone native. I’ve kept survivors company, and I’ve killed them myself. I’ve been kind and cruel. I’ve been secretive and confiding. I’ve seen survivals like long summers that run on into warm autumns. I’ve sat holding the hand of the last one left while they’ve said to me: “At least I still have you”.’

Revival

Revival Santa's Naughty Helpers

Santa's Naughty Helpers Chaz (Reapers MC Book 14)

Chaz (Reapers MC Book 14) Deceit (The Clans Book 4)

Deceit (The Clans Book 4) Wait on Me (Knights of Retribution MC Book 2)

Wait on Me (Knights of Retribution MC Book 2) Bossed Up (Iron Vex MC Book 2)

Bossed Up (Iron Vex MC Book 2) Booger (Reapers MC Book 3)

Booger (Reapers MC Book 3) Degrade: A Dark Mafia Romance (DeLancy Crime Family Book 1)

Degrade: A Dark Mafia Romance (DeLancy Crime Family Book 1) Chaos: A Reapers MC Boxset

Chaos: A Reapers MC Boxset Zorro (Reapers MC Book 16)

Zorro (Reapers MC Book 16) Venomous (The Clans Book 11)

Venomous (The Clans Book 11) Zane (Reapers MC Book 11)

Zane (Reapers MC Book 11) Hate on Me (Knights of Retribution MC Book 3)

Hate on Me (Knights of Retribution MC Book 3) Web of Lies

Web of Lies Hammer (Reapers Rejects MC Book 18)

Hammer (Reapers Rejects MC Book 18) Consumed: A Driven World Novel (The Driven World)

Consumed: A Driven World Novel (The Driven World) Anguish

Anguish Frost (Reapers MC Book 15)

Frost (Reapers MC Book 15) Alluring Allies

Alluring Allies Covert (The Clans Book 9)

Covert (The Clans Book 9) No Limits: A Taboo Anthology

No Limits: A Taboo Anthology Malicious: A Nomad Biker Novel (Raiders of Valhalla MC Book 1)

Malicious: A Nomad Biker Novel (Raiders of Valhalla MC Book 1) Venom's Secret (Iron Vex MC Book 4)

Venom's Secret (Iron Vex MC Book 4) Forbidden Love: Book 1 in the Mackenzie Series (Leave Me Breathless World)

Forbidden Love: Book 1 in the Mackenzie Series (Leave Me Breathless World) Twisted Steel: An MC Anthology: Second Edition

Twisted Steel: An MC Anthology: Second Edition Mouser (Reapers MC Book 9)

Mouser (Reapers MC Book 9) Sharp Edges (Full Throttle Book 2)

Sharp Edges (Full Throttle Book 2) Blackjack

Blackjack Reckless

Reckless Blood & Torment (Pins and Needles: Moscow Book 2)

Blood & Torment (Pins and Needles: Moscow Book 2) Demise (The Clans Book 13)

Demise (The Clans Book 13) Defiant (The Clans Book 6)

Defiant (The Clans Book 6) Flawed (The Clans Book 12)

Flawed (The Clans Book 12) Amara (Reapers MC Book 12)

Amara (Reapers MC Book 12) Widow (Reapers MC Book 4)

Widow (Reapers MC Book 4) Callous King (The O'Dea Crime Family Book 1)

Callous King (The O'Dea Crime Family Book 1) No Man Left Behind: A Veteran Inspired Charity Anthology

No Man Left Behind: A Veteran Inspired Charity Anthology Finley's Adoration

Finley's Adoration Sinister (Raiders of Valhalla MC Book 2)

Sinister (Raiders of Valhalla MC Book 2) Ruthless (The Clans Book 8)

Ruthless (The Clans Book 8) Filthy Valentine: A Dungeon Demons MC Prequel

Filthy Valentine: A Dungeon Demons MC Prequel Havoc- Reapers MC Boxset

Havoc- Reapers MC Boxset Mayhem: A Reapers MC Boxset

Mayhem: A Reapers MC Boxset The Absolute Book

The Absolute Book Dangerous Love (Mackenzies Book 3)

Dangerous Love (Mackenzies Book 3) Omen's Sign (Iron Vex MC Book 5)

Omen's Sign (Iron Vex MC Book 5) Call My Bluff: A Las Vegas Themed Anthology

Call My Bluff: A Las Vegas Themed Anthology Blood & Agony: A Dark Criminal Romance (Pins and Needles: Moscow Book 1)

Blood & Agony: A Dark Criminal Romance (Pins and Needles: Moscow Book 1) Tough as Steele (Steele Bros Book 1)

Tough as Steele (Steele Bros Book 1) Dixon (Reapers MC Book 10)

Dixon (Reapers MC Book 10) Stripping a Steele (Steele Bros Book 2)

Stripping a Steele (Steele Bros Book 2) Deprave (DeLancy Crime Family Book 2)

Deprave (DeLancy Crime Family Book 2) Vex's Temptation

Vex's Temptation Stripping a Steele

Stripping a Steele Dreamhunter

Dreamhunter The Trade

The Trade Against All Odds (Full Throttle Book 1)

Against All Odds (Full Throttle Book 1) Call My Bluff

Call My Bluff Sydney's Battle (Reapers Rejects MC: Second Generation Book 1)

Sydney's Battle (Reapers Rejects MC: Second Generation Book 1) The Angel's Cut

The Angel's Cut Dreamquake

Dreamquake Dreamquake: Book Two of the Dreamhunter Duet

Dreamquake: Book Two of the Dreamhunter Duet Reckoning (Skulls Renegade MC Book 5)

Reckoning (Skulls Renegade MC Book 5) Darkness (Darkest Nightmares Book 1)

Darkness (Darkest Nightmares Book 1) Switched (Sin City Fets Book 1)

Switched (Sin City Fets Book 1) After Z-Hour

After Z-Hour Axel (Reapers MC Book 17)

Axel (Reapers MC Book 17) A Visit to the House on Terminal Hill

A Visit to the House on Terminal Hill Scarred (Demons of Hell MC Book 1)

Scarred (Demons of Hell MC Book 1) Stolen Hearts: A Dark Billionaire Collection

Stolen Hearts: A Dark Billionaire Collection Promised (The Clans Book 1)

Promised (The Clans Book 1) The Trade (The Clans Book 2)

The Trade (The Clans Book 2) Revenge

Revenge Daylight

Daylight Redemption

Redemption Overzealous Alphas

Overzealous Alphas The Vintners Luck

The Vintners Luck Wake

Wake Corrupted Love: A Dark Mafia Romance (Mackenzies Book 2)

Corrupted Love: A Dark Mafia Romance (Mackenzies Book 2) Mortal Fire

Mortal Fire Reckoning

Reckoning Tough as Steele

Tough as Steele Scarred

Scarred Relentless (Skulls Renegade Book 4)

Relentless (Skulls Renegade Book 4) Billie's Kiss

Billie's Kiss Reclaimed (Skulls Renegade MC Book 6)

Reclaimed (Skulls Renegade MC Book 6) Deceptive Love: A Dark Mafia Duet (Mackenzie & Volkolv Book 1)

Deceptive Love: A Dark Mafia Duet (Mackenzie & Volkolv Book 1)