- Home

- Elizabeth Knox

The Vintners Luck

The Vintners Luck Read online

‘A one-of-a-kind novel…. many readers may respond as ecstactically to Knox’s brilliantly orignal books as they did to Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things.’ Kirkus Reviews, U.S.A.

‘The Vintner’s Luck is the product of a unique and lovely mind, someone fully conscious of the largeness, the presciousness and marvelousness of human life. Rather like Dickens.’ The Australian’s Review of Books

‘… inventive, highly original and utterly delightful…. Like a fine wine, this novel reveals its quality and charm in layers, providing richer rewards and delights the further one moves through it. After the initial rapture of experiencing good traditional storytelling peppered with great prose, it is the hidden depths that make this a rich and satisfying experience, one to savour again and again.’ New Zealand Herald

‘The power of this story lies in Knox’s ability to weave the magical, mysterious and menacing with the commonplace … Blood, grit, dust, salt, sand, feathers – characters in The Vintner’s Luck are covered in all of these, but the reader flies on the wings of Knox’s prose into heaven, out of hell, to emerge enriched on earth in 1997 at the château Vully l’Ange du Cru Jodeau.’ Evening Post

‘The Vintner’s Luck is an outstanding novel of ideas, poetically expressed yet always beliveable.’ Express

‘… pure, delicious fiction’ New Zealand Herald

‘… a delightful, thought-provoking read’ Denver Post, U.S.A.

‘There is a rich tapestry of rural France in the last century: a rising peasant class, a wavering nobility and the craft of winemaking. Knox’s imagination resembles one of those Burgundy slopes, mysteriously sunned and fed, that produce a vintage unlike any other…. Knox endows her angel with quirks, wit, temperatment, fierce desire and pain; but she never falls in the trap of making him human. Xas is always the Other, and the author exquisitely imagines him that way.’ Newsday, U.S.A.

‘Her erotically charged intrigue, which involves an earthbound wine grower named Sobran Jodeau and a winged visitor from heaven named Xas, promises a kind of sophisticated supernaturally tinged mystery embedded in the fateful soil of 19th-century France.’ The New York Times, U.S.A.

ALSO BY ELIZABETH KNOX

Tawa

Glamour and the Sea

Pomare

Treasure

The Vintner’s Luck

Elizabeth Knox

VICTORIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Victoria University of Wellington

PO Box 600 Wellington

http://www.vup.vuw.ac.nz

© Elizabeth Knox 1998

ISBN 0 86473 381 X

First published 1998

This edition published 1999

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the permission of the publishers

Printed by GP Print Ltd, Wellington

Could a stone escape from the laws of gravity? Impossible.

Impossible for evil to form an alliance with good.

Comte de Lautréamont

1808 Vin bourru (new wine)

A week after midsummer, when the festival fires were cold, and decent people were in bed an hour after sunset, not lying dry-mouthed in dark rooms at midday, a young man named Sobran Jodeau stole two of the freshly bottled wines to baptise the first real sorrow of his life. Though the festival was past, everything was singing, frogs making chamber music in the cistern near the house, and dark grasshoppers among the vines. Sobran stepped out of his path to crush one insect, watched its shiny limbs flicker then finally contract, and sat by the corpse as it stilled. The young man glanced at his shadow on the ground. It was substantial. With the moon just off full and the soil sandy, all shadows were sharp and faithful.

Sobran slid the blade of his knife between the bottle neck and cork, and slowly eased it free. He took a swig of the friand, tasted fruit and freshness, a flavour that turned briefly and looked back over its shoulder at the summer before last, but didn’t pause, even to shade its eyes. The wine turned thus for the first few mouthfuls, then seemed simply ‘a beverage’, as Father Lesy would say, the spinsterish priest from whom Sobran and his brother, Léon, had their letters. The wine’s now pure chemical power poured from Sobran’s gut into his blood. He felt miserable, over-ripe, well past any easy relief.

Céleste was the daughter of a poor widow. She worked for Sobran’s mother’s aunt, fetched between the kitchen and parlour, was quicker than the crippled maid, yet was ‘dear’: ‘Run upstairs, dear …’. Céleste kept the old lady company, sat with her hands just so, idle and attentive, while Aunt Agnès talked and wound yarn. At sixteen Sobran might have been ready to fall in love with her – now, at eighteen, it seemed his body had rushed between them. When he looked at Céleste’s mouth, her shawled breasts, the pink fingertips of her hand curled over the top of the embroidery frame as she sat stitching a hunting-scene fire-screen, Sobran’s prick would puff up like a loaf left to prove, and curve in his breeches as tense as a bent bow. Like his friend, Baptiste, Sobran began to go unconfessed for months. His brother Léon looked at him with distaste and envy, their mother shrugged, sighed, seemed to give him up. Then Sobran told his father he meant to marry Céleste – and his father refused him permission.

The elder Jodeau was angry with his wife’s family. Why, he wanted to know, hadn’t his son been told? The girl didn’t exactly set snares, but she was fully conscious of her charms. Sobran was informed that Céleste’s father had died mad – was quite mad for years, never spoke, but would bark like a dog. Then at midsummer an uncle, in his cups, put a tender arm around Sobran’s shoulder and said don’t – don’t go near her, he could see how it was, but that cunt was more a pit than most, a pit with slippery sides. ‘Mark my words.’

At the service after midsummer, in a church full of grey faces, queasiness, and little contrition, Céleste had looked at Sobran, and seemed to know he knew – not that he’d either asked or promised anything – but her stare was full of scorn, and seemed to say, ‘Some lover you are.’ Sobran had wanted to weep, and wanted, suddenly, not to overcome Céleste, to mount a marital assault, but to surrender himself. And, wanting, he ached all over. When Céleste spoke to him after the service there was ice in her mouth. And when, in his greataunt’s parlour, she handed him a glass of Malaga, she seemed to curse him with her toast – ‘Your health’ – as though it was his health that stood between them.

Sobran got up off the ground and began to climb towards the ridge. The vineyard, Clos Jodeau, comprised two slopes of a hill that lay in the crooked arm of a road which led through the village of Aluze and on past Château Vully on the banks of the river Saône. At the river the road met with a greater road, which ran north to Beaune. When the two slopes of Clos Jodeau were harvested, the grapes of the slope that turned a little to the south were pressed at Jodeau, and the wine stored in the family’s small cellar. The remainder of the harvested grapes were sold to Château Vully. The wine of Clos Jodeau was distinctive and interesting, and lasted rather better than the château’s.

On the ridge that divided the slopes grew a row of five cherry trees. It was for these that Sobran made, for their shelter, and an outlook. Inside his shirt and sitting on his belt, the second bottle bumped against his ribs. He watched his feet; and the moon behind, over the house, pushed his crumbling shadow up the slope before him.

Last Sunday he had left Aunt Agnès’s door before his family, only to go around the back to look in the door to the kitchen, where he knew Céleste had taken refuge. The door stood open. She was stooped over a sieve and pail as the cook poured soured milk into a cheese cloth to catch the curds. Céleste gathered the corn

ers of the cloth and lifted it, dripping whey. She wrung it over the bucket. Then she saw Sobran, gave the cloth another twist and came to the door with the fresh cheese dripping on the flags and on to her apron. Her hands, slick with whey and speckled with grainy curds, didn’t pause – as she looked and spoke one hand gripped and the other twisted. She told him he must find himself a wife. In her eyes he saw fury that thickened their black, her irises so dark the whites seemed to stand up around them like, in an old pan, enamel around spots worn through to iron. His desire took flight, fled but didn’t disperse. Sobran knew then that he wanted forgiveness and compassion – her forgiveness and compassion, and that nothing else would do.

Sobran paused to drink, drank the bottle off and dropped it. He was at the cherry trees; the rolling bottle scattered some fallen fruit, some sunken and furred with dusty white mould. The air smelled sweet, of fresh and fermenting cherries and, oddly strong here, far from the well, a scent of cool fresh water. The moonlight was so bright that the landscape had colour still.

Someone had set a statue down on the ridge. Sobran blinked and swayed. For a second he saw what he knew – gilt, paint and varnish, the sculpted labial eyes of a church statue. Then he swooned while still walking forward, and the angel stood quickly to catch him.

Sobran fell against a warm, firm pillow of muscle. He lay braced by a wing, pure sinew and bone under a cushion of feathers, complicated and accommodating against his side, hip, leg, the pinions split around his ankle. The angel was breathing steadily, and smelled of snow. Sobran’s terror was so great that he was calm, a serenity like that a missionary priest had reported having felt when he found himself briefly in the jaws of a lion. There was an interval of warm silence; then Sobran saw that the moon was higher and felt that his pulse and the angel’s were walking apace.

Sobran looked up.

The angel’s youth and beauty were a mask, superficial, and all that Sobran could see. And there was a mask on the mask, of watchful patience. The angel had waited some time to be looked at, after all. Its expression was open and full of curiosity. ‘You slept for a while,’ the angel said, then added, ‘No, not a faint – you were properly asleep.’

Sobran wasn’t afraid any more. This angel had been sent to him, obviously, not for comfort, but counsel, surely. Yet if Sobran confided nothing, and received no advice, the way he felt – enfolded, weak, warm in an embrace itself as invigorating as the air immediately over a wild sea – that alone seemed sufficient for now and for ever.

‘I can sit,’ Sobran said, and the angel set him upright. He felt the callused palms and soft wings brace, then release him. Then very slowly, as though knowing it might frighten, the angel raised his wings up and forward – they weren’t as white as his skin, or the creamy silk he wore – and settled himself, the wings crossed before him on the ground, so that only his shoulders, head and neck were visible. When the angel released him, the world came back: Sobran heard the grasshoppers, and a dog bark down the valley at the house of Baptiste Kalmann, his friend. He recognised the dog’s voice – Baptiste’s favourite, the loyal Aimée.

Sobran told the angel about his love troubles, spoke briefly and economically, as though he paid for the privilege of a hearing. He told of his love, his parent’s prohibition, and Céleste’s father’s madness. He said nothing offensive, nothing about his body.

The angel was thoughtful. He looked off into the shadow at the base of a vine where, following his gaze, Sobran saw the second bottle lay. He stretched for it, wiped the grit from its sides and offered it to the angel, who took it, covered the cork with his palm and, with no apparent use of force, drew it forth. The angel tilted the bottle to his mouth and tasted. Sobran watched the throat move, and light catch or come into a mark on the angel’s side, on his ribs, right under his raised arm – a twisted shape – a scar or tattoo like two interlocked words, one of which flushed briefly with a colour like light through the flank of a raised wave.

‘A young wine,’ the angel said. ‘Reserve a bottle and we can drink it together when it’s old.’ He handed the bottle back. When Sobran put it to his mouth he felt the bottle neck, warm and wet. Again he tasted the wine’s quick backward look, its spice – flirtation and not love.

‘Was he mad, her father?’ the angel asked.

Sobran licked his fingers, touched his own brow and made a hot stove hiss, as his grandmother had used to. ‘Barked like a dog.’

‘At the moon, or at people he didn’t like?’

Sobran blinked, then laughed and the angel laughed with him – a dry, pretty laugh. ‘I’d look into that further if I were you,’ the angel said.

‘This business of tainted blood,’ Sobran said. ‘There are so many stories of gulled brides and bridegrooms. Men or women who watch their own good corrupt and ail in their children.’ He offered the wine again. The angel held up a refusing hand.

‘It’s too young, I know,’ Sobran apologised.

‘Do you suppose I live only on thousand-year eggs?’

Sobran looked puzzled, and the angel explained. ‘In Szechuan, China, they bury eggs in ash – for a long while – then eat them, ash-coloured eggs.’

‘A thousand years?’

The angel laughed. ‘Do you think people could lay by, or wait so long to consume, or even remember where they had stored, anything, after a thousand years, whether appetising, precious, or lethal?’

The young man blushed, thinking that the angel was hinting at the Host, the thousand-year blessing which hadn’t passed Sobran’s lips for five Sundays now. ‘Forgive me,’ Sobran said.

‘The wine?’

‘I haven’t received communion for five weeks.’

The angel said, flatly, ‘Oh.’ He thought a little, then got up, wrapped one arm about the trunk of the cherry tree and, with his other hand, hauled down a limb. The branch stooped till its leaves brushed Sobran’s hair. The man picked some fruit, three on one stem, and the angel let the limb up again gently, his strength direct and dexterous. He sat, resettled his wings.

Sobran ate, his tongue separating the stones from sweet flesh and rolling them clean.

The angel said, ‘You don’t really know what Céleste knows, or what she thinks. You should just let her talk to you. Speak plainly, then simply listen. If the laws by which I have to live were numbered, that would be my first.’

A small crack opened in Sobran’s self-absorption, his infantile certainty that the night was there to nourish and the angel to guide and comfort him. He said, ‘Your first law would be our first commandment.’

‘All angels love God,’ the angel said, ‘and have no other. He is our north. Adrift on the dark waters still we face Him. He made us – but He is love, not law.’ The angel drew breath to say something further, but stopped, breath caught and lips parted. The wind got up and brushed the cherry trees, turned some of the angel’s top feathers up to show paler down. The angel’s eyes moved and changed, so that for a moment, Sobran expected to see the small green flames he often caught in the eyes of the farm cats.

Baptiste’s Aimée was barking again, as if at a persistent prowling fox. Sobran thought of foxes, then that God was listening, that His ear was inclined to the hillside.

The angel stood abruptly – a soldier surprised by an officer, jumping up to give a salute. Sobran flinched as another gust pressed the trees. The angel said, ‘On this night next year I will toast your marriage.’ Then the wind rose up in a whirling column, semi-solid with leaves, twigs and dust. The whirlwind reared, snakelike, and swallowed the angel so that Sobran saw the figure turning, face wrapped in his black hair and white clothes wrung hard against his body. The angel’s wings snapped open, a slack sail suddenly fully fed, then angel and whirlwind were a league away and above, a dark blur in the clear sky. The wind dropped. Leaves, earth, twigs, and a few black-tipped, fawn feathers sprinkled down over the northern slope of the vineyard.

The following day Sobran collected those feathers, and tied two by dark yarn to the topside o

f the rafters above his bed. The third, eighteen inches long, he put to use as a quill. Although it wouldn’t trim down, it made a fine enough line. At the kitchen table, surrounded by his family, but in secret, since all but his brother were unlettered, Sobran wrote to Céleste. He dipped, watched the ink penetrate the feather’s long chamber of air, wrote Céleste’s name, then of his clumsiness and their consequent misunderstanding. He paused to wonder at his spelling, and ran the plume through his mouth, tasting fresh snow, which made his mouth tender as he dipped once more and wrote to beg a meeting.

1809 Vin de coucher (nuptial wine)

After midnight, with the bottle unopened beside him, Sobran lay on his back on top of the ridge and looked at the sky. High cloud formed an even film from horizon to horizon, through which the full moon showed, hugely haloed in rose, steely blue and bronze. It was the kind of moon that made his mother cross herself. But to Sobran it was simply a spectacle. He was happy and relaxed, his shirt open to air his skin and his arms under his head. He was sated. He had gone to bed early, made love, then got up and washed – it wouldn’t do to meet an angel while glazed in places with love’s juices, like an egg-white coated Michaelmas bun. But the satisfaction wouldn’t wash away. Sobran smiled, slit his eyes and showed his throat to that airy wheel of moon-halo – a happy, animal homage.

There was a creak, like the rigging on a ship, a variable whistling, and the angel dropped down beside him, breathing hard. Sobran sat up and they grinned at each other. The angel’s hair was stiff with frost, and sheets of watery ice were sliding off his steaming wings. He brushed at them with one hand, dripped, panted, laughed, explained that he’d been flying high and then handed Sobran a square, dark glass bottle. Xynisteri, he said, a white wine from Cyprus. Sobran should drink it with his wife. Then he added, soberly, ‘I’m confident that you have a wife.’

Revival

Revival Santa's Naughty Helpers

Santa's Naughty Helpers Chaz (Reapers MC Book 14)

Chaz (Reapers MC Book 14) Deceit (The Clans Book 4)

Deceit (The Clans Book 4) Wait on Me (Knights of Retribution MC Book 2)

Wait on Me (Knights of Retribution MC Book 2) Bossed Up (Iron Vex MC Book 2)

Bossed Up (Iron Vex MC Book 2) Booger (Reapers MC Book 3)

Booger (Reapers MC Book 3) Degrade: A Dark Mafia Romance (DeLancy Crime Family Book 1)

Degrade: A Dark Mafia Romance (DeLancy Crime Family Book 1) Chaos: A Reapers MC Boxset

Chaos: A Reapers MC Boxset Zorro (Reapers MC Book 16)

Zorro (Reapers MC Book 16) Venomous (The Clans Book 11)

Venomous (The Clans Book 11) Zane (Reapers MC Book 11)

Zane (Reapers MC Book 11) Hate on Me (Knights of Retribution MC Book 3)

Hate on Me (Knights of Retribution MC Book 3) Web of Lies

Web of Lies Hammer (Reapers Rejects MC Book 18)

Hammer (Reapers Rejects MC Book 18) Consumed: A Driven World Novel (The Driven World)

Consumed: A Driven World Novel (The Driven World) Anguish

Anguish Frost (Reapers MC Book 15)

Frost (Reapers MC Book 15) Alluring Allies

Alluring Allies Covert (The Clans Book 9)

Covert (The Clans Book 9) No Limits: A Taboo Anthology

No Limits: A Taboo Anthology Malicious: A Nomad Biker Novel (Raiders of Valhalla MC Book 1)

Malicious: A Nomad Biker Novel (Raiders of Valhalla MC Book 1) Venom's Secret (Iron Vex MC Book 4)

Venom's Secret (Iron Vex MC Book 4) Forbidden Love: Book 1 in the Mackenzie Series (Leave Me Breathless World)

Forbidden Love: Book 1 in the Mackenzie Series (Leave Me Breathless World) Twisted Steel: An MC Anthology: Second Edition

Twisted Steel: An MC Anthology: Second Edition Mouser (Reapers MC Book 9)

Mouser (Reapers MC Book 9) Sharp Edges (Full Throttle Book 2)

Sharp Edges (Full Throttle Book 2) Blackjack

Blackjack Reckless

Reckless Blood & Torment (Pins and Needles: Moscow Book 2)

Blood & Torment (Pins and Needles: Moscow Book 2) Demise (The Clans Book 13)

Demise (The Clans Book 13) Defiant (The Clans Book 6)

Defiant (The Clans Book 6) Flawed (The Clans Book 12)

Flawed (The Clans Book 12) Amara (Reapers MC Book 12)

Amara (Reapers MC Book 12) Widow (Reapers MC Book 4)

Widow (Reapers MC Book 4) Callous King (The O'Dea Crime Family Book 1)

Callous King (The O'Dea Crime Family Book 1) No Man Left Behind: A Veteran Inspired Charity Anthology

No Man Left Behind: A Veteran Inspired Charity Anthology Finley's Adoration

Finley's Adoration Sinister (Raiders of Valhalla MC Book 2)

Sinister (Raiders of Valhalla MC Book 2) Ruthless (The Clans Book 8)

Ruthless (The Clans Book 8) Filthy Valentine: A Dungeon Demons MC Prequel

Filthy Valentine: A Dungeon Demons MC Prequel Havoc- Reapers MC Boxset

Havoc- Reapers MC Boxset Mayhem: A Reapers MC Boxset

Mayhem: A Reapers MC Boxset The Absolute Book

The Absolute Book Dangerous Love (Mackenzies Book 3)

Dangerous Love (Mackenzies Book 3) Omen's Sign (Iron Vex MC Book 5)

Omen's Sign (Iron Vex MC Book 5) Call My Bluff: A Las Vegas Themed Anthology

Call My Bluff: A Las Vegas Themed Anthology Blood & Agony: A Dark Criminal Romance (Pins and Needles: Moscow Book 1)

Blood & Agony: A Dark Criminal Romance (Pins and Needles: Moscow Book 1) Tough as Steele (Steele Bros Book 1)

Tough as Steele (Steele Bros Book 1) Dixon (Reapers MC Book 10)

Dixon (Reapers MC Book 10) Stripping a Steele (Steele Bros Book 2)

Stripping a Steele (Steele Bros Book 2) Deprave (DeLancy Crime Family Book 2)

Deprave (DeLancy Crime Family Book 2) Vex's Temptation

Vex's Temptation Stripping a Steele

Stripping a Steele Dreamhunter

Dreamhunter The Trade

The Trade Against All Odds (Full Throttle Book 1)

Against All Odds (Full Throttle Book 1) Call My Bluff

Call My Bluff Sydney's Battle (Reapers Rejects MC: Second Generation Book 1)

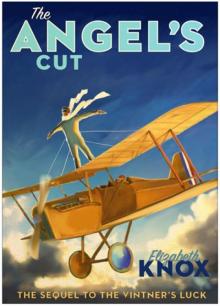

Sydney's Battle (Reapers Rejects MC: Second Generation Book 1) The Angel's Cut

The Angel's Cut Dreamquake

Dreamquake Dreamquake: Book Two of the Dreamhunter Duet

Dreamquake: Book Two of the Dreamhunter Duet Reckoning (Skulls Renegade MC Book 5)

Reckoning (Skulls Renegade MC Book 5) Darkness (Darkest Nightmares Book 1)

Darkness (Darkest Nightmares Book 1) Switched (Sin City Fets Book 1)

Switched (Sin City Fets Book 1) After Z-Hour

After Z-Hour Axel (Reapers MC Book 17)

Axel (Reapers MC Book 17) A Visit to the House on Terminal Hill

A Visit to the House on Terminal Hill Scarred (Demons of Hell MC Book 1)

Scarred (Demons of Hell MC Book 1) Stolen Hearts: A Dark Billionaire Collection

Stolen Hearts: A Dark Billionaire Collection Promised (The Clans Book 1)

Promised (The Clans Book 1) The Trade (The Clans Book 2)

The Trade (The Clans Book 2) Revenge

Revenge Daylight

Daylight Redemption

Redemption Overzealous Alphas

Overzealous Alphas The Vintners Luck

The Vintners Luck Wake

Wake Corrupted Love: A Dark Mafia Romance (Mackenzies Book 2)

Corrupted Love: A Dark Mafia Romance (Mackenzies Book 2) Mortal Fire

Mortal Fire Reckoning

Reckoning Tough as Steele

Tough as Steele Scarred

Scarred Relentless (Skulls Renegade Book 4)

Relentless (Skulls Renegade Book 4) Billie's Kiss

Billie's Kiss Reclaimed (Skulls Renegade MC Book 6)

Reclaimed (Skulls Renegade MC Book 6) Deceptive Love: A Dark Mafia Duet (Mackenzie & Volkolv Book 1)

Deceptive Love: A Dark Mafia Duet (Mackenzie & Volkolv Book 1)