- Home

- Elizabeth Knox

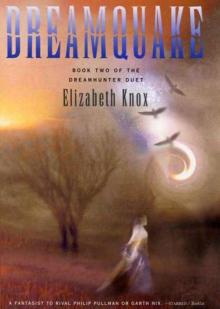

Dreamquake Page 2

Dreamquake Read online

Page 2

Grace collected herself and went on. She reached the top of the stairs and saw her daughter. Rose’s jaw went slack, and she took a step back, apparently appalled at her mother’s appearance. Grace ran to Rose, took her hands, and scanned her face. Rose was unhurt—her lips were mauve, but, Grace recalled, that was only the stain of the musk creams she had been nibbling since lunch.

The terrible howling had stopped. Behind the Opera’s doors, people had begun to call out for help—a sane, human clamor. A few started to spill out onto the balconies.

The door of the Hame Suite opened, and Laura emerged, her face white and mouth bloody. She was clumsily unwinding bandages from her hands.

Grace called to her. Laura looked at her aunt, her expression closed and remote.

There was a loud crash from the auditorium. Grace turned and saw that George Mason was in trouble. A group of men were making their way up the spiral stairs with murder in their eyes. Mason had hurled his own water jug at them. For a moment they fell back, shielding their faces with their hands, then they continued on up.

The control room was dark, but the power board was cascading sparks, by the light of which Grace could see several men from the fire watch leaning across the sill of the window that looked out over the auditorium. They appeared stunned and battered.

Grace ignored the sounds behind her—of breaking glass, and her niece calling to someone—and shouted across the auditorium to the fire watch. “Please help him!” She gestured toward Mason.

A long moment went by. The Opera’s rooms disgorged retching, staggering people. Grace yelled some more. She still had hold of her daughter, who was trying to pull away from her. Grace hung on to Rose but kept her attention on the control room and the dithering fire watchmen. She urged them to do something. In another moment George Mason would be overwhelmed. The staircase was so packed now that Grace imagined she could see the dais swaying. Finally the fire watchmen seemed to see what she wanted, and, lit by blue flashes, they began to move and act.

Grace turned back to her daughter as Rose broke away and rushed to the stairs that led to the dreamer’s door. Rose stopped, clinging to the doorframe, and peered down into the dark. The lights seemed to have failed in the stairwell. “Rose!” Grace called, and her daughter turned and came back. “Are those stairs clear?” Grace asked—she was thinking how they might avoid the angry crowd.

“No. Laura went down there. It took her,” Rose said. She was stammering with shock. “Did you see it?”

Grace frowned at Rose and touched her forehead, as though testing for a fever. “Darling, we have to hide,” Grace said gently. Then she grabbed Rose and propelled her toward the balcony of the Presidential Suite. These balconies were usually locked, but Grace was hoping that, since the President had been carried to safety, his bodyguards hadn’t bothered to close the door behind them when they fled.

The first door was not only open but broken and hanging from one hinge. The balcony was empty except for an overturned chair. Grace hustled her daughter into the suite. She pulled the door closed and bolted it.

For the next five minutes Rose and Grace hid; they cowered as an enraged crowd beat on the bolted door. Then they heard police whistles.

Rose tried to talk in stops and starts. She said to her mother, “Did you see it? What was it? Why did Laura want that? Why was she calling it to her?”

And to these incoherent questions Grace could only reply, “It was a dream, darling, just a dream. It must have seemed like that to Laura too. Just a dream. She’s not like you and me.”

When he was finally able to drag himself free from the nightmare, Sandy staggered out of bed and into his room’s cramped bathroom. He ran the cold tap and rinsed his mouth. Ribbons of blood spiraled down the drain in pink-tinged water. It was only once he’d stopped running the water that he became aware of the racket coming from the balcony beyond his door. He went out to look.

The doors of rooms around the third tier were flung open. It seemed that many people had come out only in search of a less confined space. Near Sandy two women in torn silk pajamas were leaned over the balcony rail, one gasping for air, the other scrubbing her lacerated face with blood-slick palms.

People were heading toward the stairs. Some wept and staggered as they went, others were more purposeful, pushing their way through, their faces injured and contorted, but wrathful too.

Sandy looked at himself. There was blood under his fingernails. His pajama top was open, its buttons gone or dangling by threads.

From below came sounds of a melee, crashes, shouting, and police whistles. Sandy went to the rail, leaned over, and saw his uncle. George Mason was at the top of the dreamer’s dais, facedown on churned-up bedding. Two men had hold of him by his legs and were trying to drag him into a crowd of enraged people who were fighting for space on the spiral stairs. Sandy saw a few members of the Opera’s fire watch among the crowd and, at the foot of the stairs, a bunch of police officers fighting their way up, swinging their truncheons.

Sandy stood frozen, gripping the rail, till the police managed to reach his uncle and wrap both a quilt and their uniformed bodies around him.

Another clutch of police came into sight in the main auditorium. They fought their way through the crowd toward the main exit. Grace Tiebold was in their midst, the train of her opulent gown in tatters, her cheeks and throat smeared with blood.

Reinforcements arrived. Police poured onto the auditorium floor. Sandy heard a gunshot and saw glass rain down from a hole punched in the Opera’s stained-glass dome. He flinched back from the rail and joined the crowd pouring down the nearest staircase.

There was a press of people on the stairs. Sandy was surrounded by the sound of weeping. For a brief moment he was snagged in a group of men in suits who seemed to be trying to decide whether to continue up or turn and follow the crowd back down. Sandy caught snatches of their talk.

“The police have her already …”

“But was it her? I think that nightmare was Hame’s Buried Alive …”

Someone elbowed Sandy in the ribs, and the men slipped ahead of him. He followed, stumbling over a dropped bowler hat.

Outside, in the Crescent Plaza, there were more bowler-hatted Regulatory Body officials. Most of them stood in little groups, turned away from the throngs of distressed people. There were ambulances and paddy wagons in the plaza, and a fire truck, the firemen passing out blankets.

Suddenly Sandy spotted a head of unmistakable bright hair. He ran toward Rose Tiebold, calling her name. He couldn’t see Laura with her. Rose turned to him. Her face was pale but unmarked. Someone grabbed Sandy by the collar of his pajamas and held him. Sandy grappled with the hand but concentrated on Rose. “Where’s Laura?”

Beside him a voice said, “This boy is a dreamhunter. You should make sure to catch any who were here.”

Sandy looked around. The man who held him was a police captain. The other man, the one issuing instructions, was the Secretary of the Interior, Cas Doran. Doran had his hand under Rose’s elbow, to comfort rather than detain her it seemed. His lips were bitten and bleeding. He didn’t look calm, but he did have an air of command, of mastery and self-mastery.

Sandy heard Doran tell the police captain that any dreamhunters who had been at the Opera would be reproducing the nightmare when they next slept.

It hadn’t occurred to Sandy that he’d taken a print of the nightmare, but now that he knew, he thought he could feel it inside him, a capsule of terror and airless darkness. He moaned.

Rose touched his hand. “Sandy, your uncle is with my mother at the city barracks,” she said.

“But where is Laura?”

Rose glanced at the man beside her. “Laura ran off. She was scared. I had bare feet, and there was glass on the stairs—or else I’d have followed her.”

Cas Doran released Rose to lay both his hands on Sandy’s shoulders. He shook him. “Who was Laura Hame with?” Doran demanded.

Sandy was puzzled—hadn’

t Doran heard what Rose had said, or did he not believe her? “She was with Miss Tiebold,” Sandy said, then added, insolent, “That’s why I’m asking Miss Tiebold where she is.”

“Laura was in bed with me,” Rose said. “We didn’t sleep. We were talking. When the screaming started, Laura got scared and bolted down the stairs to the dreamer’s door.” Rose looked from Doran to Sandy, her expression earnest and, beneath that, very alert.

Sandy wanted to find Laura. He gazed around at the people in blankets. He saw one he recognized, bundled up and shivering, Maze Plasir’s apprentice, Gavin Pinkney. Sandy noticed the odd, imploring way that Gavin stared at Secretary Doran, then dismissed it as irrelevant. He had to find Laura.

Rose was plucking at Secretary Doran’s arm. She said she wanted to go home. Her cousin would have run there. Doran shook his head. Rose was his daughter Mamie’s best friend, she must come home with him, he said. “I’ll send some people to your house to find your cousin.” Then the Secretary turned to Sandy. “As for you, Mr. Mason. The police and Regulatory Body officials are gathering exposed dream-hunters …”

Sandy was so startled that the Secretary of the Interior knew who he was that he missed the next few things the man said. Something about public safety, and a quarantine for those affected.

Doran called over one of the Dream Regulatory Body officials. Sandy thought to himself that whenever they showed up en masse like this, the officials did rather have the appearance of a private army. Doran’s private army.

“I have a dreamhunter here,” the Secretary said, and laid his heavy hand on Sandy’s shoulder once more. “And Maze Plasir’s apprentice is standing just over there. Also, Miss Tiebold tells me that her cousin, the dreamhunter Laura Hame, will have run home.”

The official gave a curt nod.

“She didn’t sleep,” Rose said, urgent. “We were talking.” Then she gave a choked laugh.

The official took hold of Sandy and walked him away. They collected Gavin Pinkney as they went. The official said, “We’ll find you some clean clothes. Then we’ll take you straight In and see if you can’t overwrite the nightmare before you have to have it again.”

Sandy realized the “clean clothes” remark was directed at Gavin, who stank of urine. The poor boy had wet himself.

Sandy craned back over his shoulder at Rose Tiebold, hoping for some communication, some sign. But she was speaking to Doran, standing with her head erect and a haughty expression on her face, as though she was somehow above even her own worries.

Sandy turned away, trudged on, and fumed. For a moment he reverted to his earlier resentful thoughts about the rich and famous Tiebolds and Hames. Then he remembered how Rose had insisted “We didn’t sleep.”

It was clear that she hadn’t, because her cheeks and mouth weren’t marked by her own fingernails. But Laura was another matter. What if the truth was the opposite of Rose’s story? What if the girls were not together, were not talking, were not both awake?

Sandy stumbled. The official made an impatient noise and jerked him upright. “Leave me alone!” Sandy said, and drove his shoulder into the man’s side. The man wheezed, then, “You’re not about to give me trouble, Mason, are you?”

Sandy glowered but let himself be led on. His head was spinning—in fact, the whole of him seemed to be spinning, speeding up, draining away down some great, dark whirlpool. For he knew Laura had been chewing Wakeful. She’d taken the drug and walked some distance out of the Place carrying a nightmare. She’d kept her nightmare fresh and had delivered it, overpowering her aunt, and Sandy’s uncle, and Sandy, and every other sleeping soul in the Opera that night.

When the Mason boy had left them, Doran asked Rose, “Is that your cousin’s beau?”

The girl replied, “I’m sure I wouldn’t know,” every inch a Founderston Girls’ Academy senior asserting her sense of what was proper.

Cas Doran realized with a small shock that he knew very well what Rose’s life was like. She had the kind of agile spirit to be found in those who straddled very different worlds. She attended a fashionable school, had all the manners of a nice young lady—in other words, she prickled with barbed boundaries—but she was also from a dreamhunting family and party to the daily phantasmagoria of life with dreamhunters, to their frequent exhaustion and feverish wildness.

These dreamhunters—they were his. His responsibility, his study, his stock-in-trade. But Cas Doran was not a dream-hunter, nor was anyone in his family. He lived a regular domestic life in a household run by a refined woman—herself a graduate of the Girls’ Academy. And that was how he knew what Rose Tiebold’s life was like, how contradictory it must be. Because, even given the differences in their ages and occupations, this girl was in some ways like him.

Secretary Doran’s car came through the crowd. The chauffeur stood up and called to his employer.

“Come,” said Doran to Rose, his tone gentle but managing.

Rose went with him. He spoke soothingly. He said that everything would be all right. He helped her into the car. Its interior smelled pleasantly of new leather. Rose realized that there had been some terrible smells, as well as terrible sights, in the plaza.

The car began to move again, easing its way through the thronging people. There were seething shadows on the plaza,interrupting the lights from streets and houses. Rose stared at Doran’s profile. In the light ghosting over his face, Doran looked grim and intent, like someone getting ready for a fight. Then he turned and smiled at her.

Rose knew she’d do everything she could to keep people from guessing that it was her cousin’s nightmare. Before too long she’d speak to Laura, then she’d know why her cousin had done it. There would be a reason, some kind of sense. Rose suspected it had something to do with the letter Laura had torn up, a last letter from her missing father.

The letter had, for some reason unfathomable at the time, been partly buried in a large amount of sand in Laura’s bedroom at Summerfort. Laura had been into the Place illicitly, looking for clues to why her father had disappeared. She was back in Summerfort when Rose and Rose’s father, Chorley, had found her. Laura had kept them out of her bedroom; then, when she had finally opened the door, they’d found her standing up to her ankles in a pile of sand. The envelope that held the letter was sticking out of it.

Sand!

When, that very night—St. Lazarus’s Eve—the howls of terror had wound down, Rose had seen her cousin emerge from the Hame Suite and stand for a moment unwinding bandages from her hands. Laura had looked up at Rose, then seemed to dismiss her. She began to call. What she shouted sounded like nonsense, but it was a name. At her call a monster had come running. A great statue in the shape of a man—a beautifully muscled, nobly serene man. A man apparently made of sand. The monster had swept Laura up in his arms and run to the stairs down to the dreamer’s door. Rose had tried to break away from her mother to follow them. But Rose’s mother had kept a firm hold on her. Then Rose, straining after Laura,had seen something. She saw the name Laura had called scored in the sand on the back of the monster’s neck. Four letters: N O W N.

Rose was trembling. Secretary Doran touched her arm and said, “How are you, Rose?” Then, “We’re nearly home.”

There was no one in the world Rose was closer to than Laura, but Rose had known nothing of any of this—the nightmare or the monster. She felt herself shrinking. She didn’t know anything. All her schoolmates thought she was a bit of a hero, but she wasn’t. She was baffled, and in the dark.

2

AURA’S SANDMAN CARRIED HER ALL NIGHT. HE WALKED FOR TWENTY MILES, FOLLOWING THE RAIL LINE SOUTHwest from Founderston, traveling along the railbed with long, rocking strides. Laura was careful to keep her eyes open. She was afraid of waking up in her dream again, of opening her eyes on blackness and the chilly embrace of a satin shroud.

They left the tracks at the small train stop near Marta Hame’s house. They didn’t follow the road, for it was getting light, a dull twilight rinsed by dri

zzle.

As Nown clambered up a hillside, Laura heard sheep pattering away from them. She saw the flock pour down a slope together and flow into the groove of a gully, like raindrops on a large leaf spilling to pool at the stem.

Nown pressed down the top wire of a fence, and the whole thing strained, twanging along its length. He stepped over it.

At the edge of Aunt Marta’s yard, Laura told Nown to stop. She slid from his arms, and he steadied her till she found her footing. She said, “You hide yourself. But stay near.” Then she recalled that she had set him free.

Nown had helped her do what her father had asked in the letter he left for her. Laura had hated having to catch Buried Alive and overdream her unsuspecting Aunt Grace. As she had gone about it, she had come to understand that her sand-man had doubts about what she was doing. When he’d tried to speak to her, she had silenced him.

She had made him; he was her servant, bound to obey her by rules she knew she didn’t fully understand. But she did understand the most simple rules of the spell that had made him. She knew that if she erased the W in his name, made it NON instead of NOWN, he would fall apart, as her father’s sandman had. And she knew that if, instead, she erased the first N in his name, he’d be his own—free. With Nown’s help, Laura had completed the task her father had set her. Then she found that what she wanted next wasn’t obedience but guidance and wisdom—and to be cherished.

Revival

Revival Santa's Naughty Helpers

Santa's Naughty Helpers Chaz (Reapers MC Book 14)

Chaz (Reapers MC Book 14) Deceit (The Clans Book 4)

Deceit (The Clans Book 4) Wait on Me (Knights of Retribution MC Book 2)

Wait on Me (Knights of Retribution MC Book 2) Bossed Up (Iron Vex MC Book 2)

Bossed Up (Iron Vex MC Book 2) Booger (Reapers MC Book 3)

Booger (Reapers MC Book 3) Degrade: A Dark Mafia Romance (DeLancy Crime Family Book 1)

Degrade: A Dark Mafia Romance (DeLancy Crime Family Book 1) Chaos: A Reapers MC Boxset

Chaos: A Reapers MC Boxset Zorro (Reapers MC Book 16)

Zorro (Reapers MC Book 16) Venomous (The Clans Book 11)

Venomous (The Clans Book 11) Zane (Reapers MC Book 11)

Zane (Reapers MC Book 11) Hate on Me (Knights of Retribution MC Book 3)

Hate on Me (Knights of Retribution MC Book 3) Web of Lies

Web of Lies Hammer (Reapers Rejects MC Book 18)

Hammer (Reapers Rejects MC Book 18) Consumed: A Driven World Novel (The Driven World)

Consumed: A Driven World Novel (The Driven World) Anguish

Anguish Frost (Reapers MC Book 15)

Frost (Reapers MC Book 15) Alluring Allies

Alluring Allies Covert (The Clans Book 9)

Covert (The Clans Book 9) No Limits: A Taboo Anthology

No Limits: A Taboo Anthology Malicious: A Nomad Biker Novel (Raiders of Valhalla MC Book 1)

Malicious: A Nomad Biker Novel (Raiders of Valhalla MC Book 1) Venom's Secret (Iron Vex MC Book 4)

Venom's Secret (Iron Vex MC Book 4) Forbidden Love: Book 1 in the Mackenzie Series (Leave Me Breathless World)

Forbidden Love: Book 1 in the Mackenzie Series (Leave Me Breathless World) Twisted Steel: An MC Anthology: Second Edition

Twisted Steel: An MC Anthology: Second Edition Mouser (Reapers MC Book 9)

Mouser (Reapers MC Book 9) Sharp Edges (Full Throttle Book 2)

Sharp Edges (Full Throttle Book 2) Blackjack

Blackjack Reckless

Reckless Blood & Torment (Pins and Needles: Moscow Book 2)

Blood & Torment (Pins and Needles: Moscow Book 2) Demise (The Clans Book 13)

Demise (The Clans Book 13) Defiant (The Clans Book 6)

Defiant (The Clans Book 6) Flawed (The Clans Book 12)

Flawed (The Clans Book 12) Amara (Reapers MC Book 12)

Amara (Reapers MC Book 12) Widow (Reapers MC Book 4)

Widow (Reapers MC Book 4) Callous King (The O'Dea Crime Family Book 1)

Callous King (The O'Dea Crime Family Book 1) No Man Left Behind: A Veteran Inspired Charity Anthology

No Man Left Behind: A Veteran Inspired Charity Anthology Finley's Adoration

Finley's Adoration Sinister (Raiders of Valhalla MC Book 2)

Sinister (Raiders of Valhalla MC Book 2) Ruthless (The Clans Book 8)

Ruthless (The Clans Book 8) Filthy Valentine: A Dungeon Demons MC Prequel

Filthy Valentine: A Dungeon Demons MC Prequel Havoc- Reapers MC Boxset

Havoc- Reapers MC Boxset Mayhem: A Reapers MC Boxset

Mayhem: A Reapers MC Boxset The Absolute Book

The Absolute Book Dangerous Love (Mackenzies Book 3)

Dangerous Love (Mackenzies Book 3) Omen's Sign (Iron Vex MC Book 5)

Omen's Sign (Iron Vex MC Book 5) Call My Bluff: A Las Vegas Themed Anthology

Call My Bluff: A Las Vegas Themed Anthology Blood & Agony: A Dark Criminal Romance (Pins and Needles: Moscow Book 1)

Blood & Agony: A Dark Criminal Romance (Pins and Needles: Moscow Book 1) Tough as Steele (Steele Bros Book 1)

Tough as Steele (Steele Bros Book 1) Dixon (Reapers MC Book 10)

Dixon (Reapers MC Book 10) Stripping a Steele (Steele Bros Book 2)

Stripping a Steele (Steele Bros Book 2) Deprave (DeLancy Crime Family Book 2)

Deprave (DeLancy Crime Family Book 2) Vex's Temptation

Vex's Temptation Stripping a Steele

Stripping a Steele Dreamhunter

Dreamhunter The Trade

The Trade Against All Odds (Full Throttle Book 1)

Against All Odds (Full Throttle Book 1) Call My Bluff

Call My Bluff Sydney's Battle (Reapers Rejects MC: Second Generation Book 1)

Sydney's Battle (Reapers Rejects MC: Second Generation Book 1) The Angel's Cut

The Angel's Cut Dreamquake

Dreamquake Dreamquake: Book Two of the Dreamhunter Duet

Dreamquake: Book Two of the Dreamhunter Duet Reckoning (Skulls Renegade MC Book 5)

Reckoning (Skulls Renegade MC Book 5) Darkness (Darkest Nightmares Book 1)

Darkness (Darkest Nightmares Book 1) Switched (Sin City Fets Book 1)

Switched (Sin City Fets Book 1) After Z-Hour

After Z-Hour Axel (Reapers MC Book 17)

Axel (Reapers MC Book 17) A Visit to the House on Terminal Hill

A Visit to the House on Terminal Hill Scarred (Demons of Hell MC Book 1)

Scarred (Demons of Hell MC Book 1) Stolen Hearts: A Dark Billionaire Collection

Stolen Hearts: A Dark Billionaire Collection Promised (The Clans Book 1)

Promised (The Clans Book 1) The Trade (The Clans Book 2)

The Trade (The Clans Book 2) Revenge

Revenge Daylight

Daylight Redemption

Redemption Overzealous Alphas

Overzealous Alphas The Vintners Luck

The Vintners Luck Wake

Wake Corrupted Love: A Dark Mafia Romance (Mackenzies Book 2)

Corrupted Love: A Dark Mafia Romance (Mackenzies Book 2) Mortal Fire

Mortal Fire Reckoning

Reckoning Tough as Steele

Tough as Steele Scarred

Scarred Relentless (Skulls Renegade Book 4)

Relentless (Skulls Renegade Book 4) Billie's Kiss

Billie's Kiss Reclaimed (Skulls Renegade MC Book 6)

Reclaimed (Skulls Renegade MC Book 6) Deceptive Love: A Dark Mafia Duet (Mackenzie & Volkolv Book 1)

Deceptive Love: A Dark Mafia Duet (Mackenzie & Volkolv Book 1)